As the US flounders, can the EU gain influence in its near neighbourhood?

Morocco has the world's oldest peace treaty with the US and is home to America's oldest consulate. Two-thirds of its trade may be with the EU, but Rabat is more influenced by Washington than Brussels.

Last week, I spent the Easter break in Morocco, travelling around the country from the scorching hot Sahara in the Southeast to the windy Mediterranean gateway of Tangier in the Northwest. During the visit, I was keen to get a feel for how people view Morocco’s foreign policy these days given the new era we are entering with the Trump regime in America. The Middle East and North Africa may be ‘Europe’s backyard’ (with a whole “DG Near” directorate dedicated to it within the European Commission), but for the past 70 years it is the United States that has guided foreign policy in the region, not Europe. Ever since Washington slapped down Britain and France in the Suez crisis of 1956, the region’s former colonial powers have been progressively more and more irrelevant there. Watching Europe’s impotence and irrelevance following the October 7th attacks and Israel’s bombardment of Gaza over the past year and a half has made this painfully clear.

But US influence in the world has nosedived over the first 100 days of the Trump administration. The regime’s indiscriminate tariffs have enraged countries globally and caused many governments to think about shifting their foreign policy orientation toward China. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has tried to seize the moment by advertising the EU as a more stable, rule-following and values-based alternative to both Washington and Beijing. “In a more and more unpredictable global environment, countries are lining up to work with us," she told Politico last week. The global order is "shifting more deeply than at any time since the Cold War ended,"she said. “In the middle of the chaos, Europe stands firm, grounded in values, ready to shape what comes next.”

But how much Europe can actually shape what comes next is very uncertain. The foreign policy divisions within the EU have prevented it from becoming a serious player on the global stage. National governments have steadfastly refused to give Brussels the authority to speak on behalf of the EU with one voice. Von der Leyen insists that the EU is right now being taken seriously as a power player in capitals as far away as Brasilia, Ontario, Tokyo and Canberra. The reality is that outside of trade and economics, the EU still has very limited political influence even in its own backyard - let alone on the other side of the world. For a country like Morocco, where a third of the population speaks French and French companies have major influence, there is obviously big potential for improvement in terms of influence. The Moroccan diaspora has also fostered deep cultural ties with Europe because of migration following the guest worker programs of the 1960s. Moroccans are the second-biggest foreign nationality in the EU capital, with people of Moroccan descent comprising 15% of Brussels residents. But that potential is still stymied by the hangover from France’s colonial legacy, something which is the case for every Middle Eastern country when it comes to France, Britain and Spain.

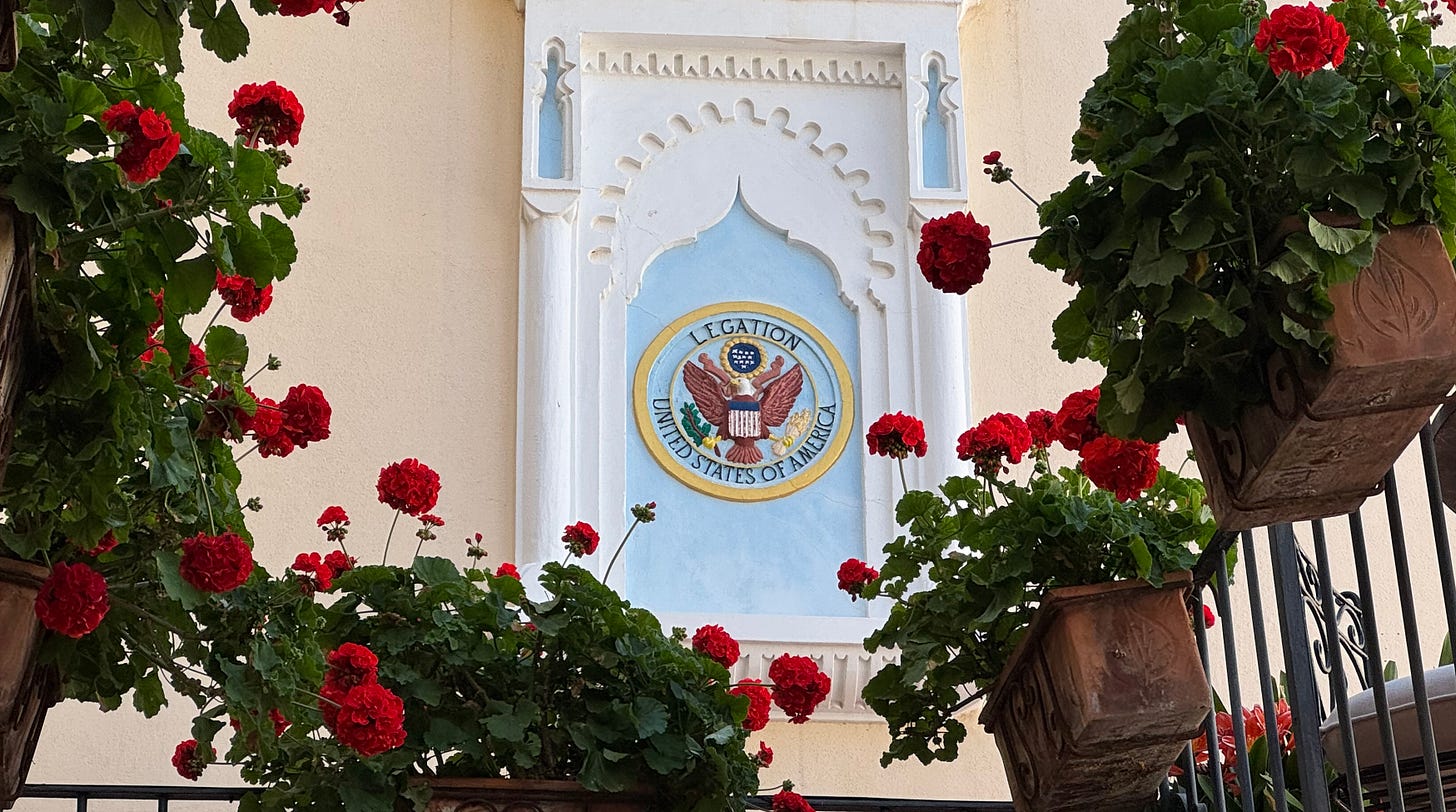

The United States, unburdened by this colonial legacy, presented itself in the 1950s and 60s as an ally in the struggle for independence from the Europeans. The newly-independent nations, some with longer histories than others, thus came to trust the US more than their neighbours in Europe. Morocco and the US had historical reasons for this trust. Morocco was the first country in the world to recognise US independence in 1777 - even before the French. The Moroccan-American Treaty of Peace and Friendship establishing formal diplomatic and commercial relations in 1786 is the oldest unbroken treaty relationship in US history (though you could argue it ceased to be in effect during the French protectorate from 1912 to 1956). The American Legation in Tangier was the first American public property abroad and today it’s the only US National Historic Landmark in a foreign country. In 1956, the US sought to return the favour of Morocco’s early recognition of America by successfully pressuring France to end its protectorate over Morocco (though the US didn’t seem too bothered by their friend losing its sovereignty when France took it over in 1912).

But lately things have changed. Morocco has been badly burned by the US-brokered peace agreement it signed with Israel during Trump’s first term. In exchange for Morocco recognising Israel’s existence and establishing full diplomatic relations (along with direct flights from Rabat to Tel Aviv), both Israel and the US agreed to recognise Morocco’s possession of the disputed territory of Western Sahara. Morocco was even ready to re-enter the Eurovision Song Contest as a result of the treaty (though Arab countries are all eligible to participate as members of the European Broadcasting Union, they do not compete in Eurovision because they would have to air the Israeli entry). However, Israel’s bombardment of Gaza in response to the October 7th attack has turned that treaty into a huge liability for Moroccan King Mohammed VI. Palestinian flags are everywhere in Morocco right now and I witnessed a large demonstration against the US-brokered treaty in Tangier just before leaving.

Because of the Israel issue and Trump’s tariffs declaring economic war on Morocco now in his second term, opinions of the US are not very high in Morocco right now. While the Alawi monarchy may still view the US as a liberator and ally, the average citizen in Morocco certainly doesn’t share the same opinion right now. There are very few Moroccans alive today who lived through France and Spain’s colonial occupation. Those resentments are now largely a thing of the past. Is this the right time for the EU to increase its influence in Morocco and the rest of the Arab world? If so, how can this be done? And if the EU doesn’t do it, who else might step into the vacuum to take the place of US leadership? Let’s look at some of the possibilities.