Brexit is hindering Europe's rearmament

The EU has been unable to lead the response to the collapse of the transatlantic alliance, necessitating ad-hoc summits in Paris and London. But the main problem is not Orban. It's Brexit.

Following last week’s crisis summit in London convened by Keir Starmer, the British prime minister told reporters that the European leaders would be meeting again “very soon”. It was hard to tell in that moment whether he meant at the emergency EU Council summit happening in Brussels four days later, where the same leaders would be meeting but without those from Britain, Canada and Norway. But when Thursday came there was no Starmer in Brussels, so it became clear he meant a future meeting in London.

If that meeting comes next month, the leaders travelling to London will need to apply in advance for an ETA visa in order to enter the UK. That’s because from April, EU citizens (except the Irish) will need to pay €12 to apply for permission to enter the UK well before they board their train or plane. It won’t present any problem for these leaders, but for their citizens it’s going to be a mess. It very obviously is not going to occur to most European travellers that they need to apply in advance for permission to enter a country with which they had free movement until just four years ago. The Eurostar terminals in Brussels and Paris are going to be a nightmare as hordes of people are denied boarding. It is just one example of the unnecessary problems that continue to be caused by the UK’s scorched-earth Brexit policy enacted over the past eight years since Brits narrowly voted to leave the EU. And it’s symbolic of the problems being encountered this month as Europe tries to rapidly set up sovereign defence after the collapse of the transatlantic alliance with the United States.

An EU bypass

I’ve noticed that the media seems to have taken it for granted that the ad-hoc defence summits called by Macron and Starmer over the past three weeks were necessary in order to avoid the veto of Trump/Putin ally Viktor Orban, the prime minister of Hungary who must be present at European Council summits. But while that is indeed a factor, the bigger reason these summits had to take place outside of Brussels was not because of Hungary, but because of the UK.

Starmer has taken an extremely cautious approach to his so-called “reset” of relations with the EU, fearful of criticism from the right-wing British press if it looks in any way like he is trying to take the UK back toward the rest of Europe. They are particularly worried about the ‘red wall’ voters (who only just recently moved back to Labour) being lured by the ascendant British far right, which is now polling in second place in the UK above the Conservatives. Starmer already attended a dinner at an informal Council summit last month and got flack for it. The calculation seems to be that him attending another EU summit so soon would be too risky for him in terms of domestic politics. So instead of attending the Brussels summit on Thursday with Zelesnkyy, he brought a select few leaders to London for a summit. Though it had been scheduled before Trump’s Oval Office attack on the Ukrainian president, events overtook it and it ended up looking like it had been convened in order to react to the shocking scenes in Washington.

Video: What's next after the Paris emergency summit?

It’s been a week that’s felt like a year in Europe, with the developments at the NBATO defence ministers summit and Munich Security Conference leading many to declare that this was the week the transatlantic alliance officially collapsed.

These ad-hoc summits are happening outside of the existing institutional infrastructure of the EU and NATO for three reasons. NATO, an American-led military protectorate, obviously makes no sense as a forum to discuss a Europe-only strategy to build up defence to shake off American dependence. Given that, attention would naturally turn to the European Union as the vehicle to coordinate that European response. The EU has every right and ability to do so under the existing treaties (contrary to popular belief, there is a defence platform of the European Union, there has just been a taboo against using it until now). But two fatal mistakes over the past decade have hobbled the EU’s ability to lead the response. The first was the failure to end unanimity voting for foreign policy issues, something asked for by citizens in the Conference on the Future of Europe four years ago but which national European leaders refused to act on. That has meant Viktor Orban can still veto measures to help Ukraine and build up an EU defence union (though, as we saw on Thursday, there are sometimes ways around that if national leaders are willing). The second mistake blocking EU action was the hard Brexit enacted by the Conservative British government following the 2016 Brexit referendum.

The Council’s empty chair

Until 2020, the EU had two big military powers: France and Britain, which both have nuclear weapons. Now, it only has one. While countries like Poland and Greece have large militaries relative to their size (because of threats from their neighbours), they cannot be considered big military powers (though Poland may be on its way). For sovereign European military command and control to be credible, it needs the UK. But because Britain isn’t in the EU any more, it means that either the UK needs to quickly develop a structure of cooperation with the EU or a whole new system for Europe’s military defence needs to be developed from scratch. As I’ve written recently, pursuing the latter path and creating some kind of European Treaty Organisation (ETO) would be completely absurd. For starters, there just isn’t the time.

There are existing institutions already set up at EU level under the Common Security and Defence Policy that are not being used, such as the EU Military Committee, the EU Defence Agency, PESCO, the Commission’s new Defence Industry Directorate-General, and the External Action Service's permanent Operation Headquarters (OHQs) for command and control. It’s all there, but Europeans have been afraid to properly use these tools for fear of undermining NATO. If NATO is now effectively dead with the lack of confidence over Article 5 (As Germany’s most-likely next chancellor has admitted), these concerns are no longer legitimate.

Trying to organise European collective defence outside of these existing structures is dooming the effort to failure. The hope is that NATO can be preserved, but it must be fundamentally restructured to be an actual alliance rather than a protectorate. That would mean that NATO has two main pillars, American and European, which are equal in power. This is possible - together European countries actually spend roughly the same as the US on defence, but this is an irrelevant bit of trivia as long as these militaries are not united. A report published by Bruegel recently found that Europe would need to spend just 1.5% of the EU’s GDP to be able to defend itself against Russia with 300,000 soldiers, but only if it was coordinated as a unified effort.

What we’re talking about here is something more than a "European NATO within Atlantic NATO”. To really equal the US, the European half needs to be attached to federated democratic institutions that can take decisions. There are ways for the UK to participate in an EU Defence Union in a limited way while still sticking to Starmer’s red lines refusing alignment with the single market. It’s not easy, but it can be done. The question is whether Starmer has the political courage to do it, or whether all of Europe has to accommodate the British prime minister’s timidity and waste time reinventing the wheel.

Ways for Britain to participate

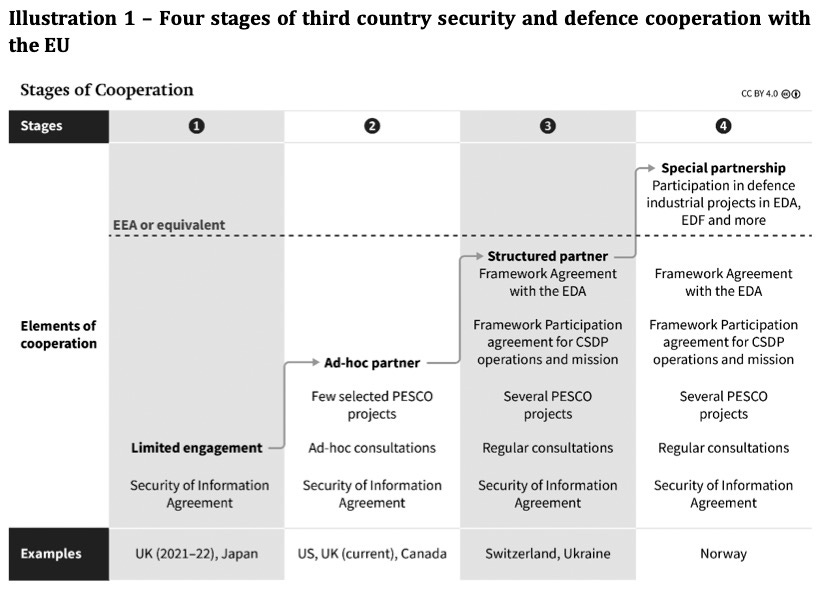

The German Institute for International and Security Affairs has just come out with a paper outlining ways in which the UK could participate in the EU’s common security and defence policy. It makes for a depressing read for those who want Europe to urgently build independent defence.

“The starting position of the EU and the UK on security and defence cooperation is, despite the large overlap in values and interests, difficult. As part of its hard Brexit agenda, the Boris Johnson government divorced the UK from any structural cooperation with the EU on foreign, security and defence policy, perceiving it as an area where bilateral and multilateral cooperation with the EU’s member states would be sufficient for the UK. Although ad-hoc cooperation between the EU and the UK picked up in wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as of early 2025 the EU has a closer security relationship with Norway, Ukraine or the US than it has with the UK.”

The EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) has designed a set of rules to govern - and limit - third country participation. The problem is they’re almost exclusively aimed at Norway, which is a pseudo-EU member state through the framework of the European Economic Area (EEA). This means that these arrangements are designed for a small country that is already deeply connected to the EU, not a large military power that is entirely outside of it.

Since the UK left the EU in 2021, the only institutionalised security relationship between the two has been the Security of Information Agreement, because negotiations for all other more substantial forms of cooperation failed. “Originally, then Prime Minister Theresa May was especially keen on reaching a security agreement,” the report notes. “In the course of the Brexit negotiations, the EU and the May government put forward several proposals for institutionalised cooperation. [But] when Boris Johnson took over as prime minister in the summer of 2019…he radically changed his political course. When negotiations began in February 2020, the British government clearly distanced itself from possible CSDP cooperation. In its own guidelines for the negotiations published on February 3, it categorically excluded the goal of any structured form of cooperation in foreign, security or defence policy. This marked a decisive shift in the UK’s approach to its security relationship with the EU.”

But Johnson is gone, and Keir Starmer is prime minister now. As part of his reset, Starmer has said he wants security cooperation with the EU. The report outlines the different options for that in the chart above, possibly to come in stages. It would require a big movement and several steps for the UK to get up to the level of Norway’s security cooperation with the EU. “There is significant leeway for deepening EU-UK security and defence cooperation on existing CSDP instruments, but also clear political and legal hurdles,” the report concludes. “In terms of expectations management, it should first be made clear that while there is such room for deepening cooperation, a coordination and cooperation on security and defence instruments is not straight-forward or a low-hanging fruit. To the contrary, as in the overall EU-UK relationship since Brexit, they require a tricky balance of compromise in finding a space for the UK in the EU’s third country relationships. Generally, cooperation becomes much more complicated and more demanding, the closer it gets to defence industrial cooperation. Here, current EU rules – as developed by the member states – allow only for full participation of EEA countries that are fully integrated into the EU’s single market, in short: Norway. A return to the single market is, of course, fully ruled out by the current Labour government.”

In other words, to get to any kind of meaningful military cooperation, either the UK or the EU will have to drop their red lines. On the British side, when I’ve talked to officials, they seem very confident that they “hold all the cards” on the military subject at least, even if the experience of the past eight years taught them that they didn’t hold the cards economically. But I think they’re underestimating the EU’s determination not to violate the integrity of the single market by allowing the UK to pick and choose its access. Continental European countries are rapidly expanding their militaries as we speak, with Germany’s shock announcement of an unprecedented rearmament last week and Poland’s reinstitution of the draft to build an army of half a million. In the short term the UK’s military might is needed to make European defence credible. But the hard Brexit that the Tories left the UK government to deal with means that solving the roadblocks that have been erected is going to take a significant amount of time. And during that time, the military imbalance between the UK and non-France EU is likely to become less lop-sided. In other words, the longer the UK waits on this, the less essential it becomes.

What is clear is that while building sovereign European defence through the EU’s institutional structures will be difficult, it is also essential. There simply isn’t time to build new structures from scratch, and the short-term ‘coalition of the willing’ framework only works as a momentary band-aid. Brexit has presented a huge problem for the European crisis response in this moment, a fact that seems to be ignored in the British media at the moment. That Council chair Antonio Costa had to call Starmer after Thursday’s emergency summit in Brussels to brief him on the outcome only highlighted the problem. There could have been movement at the Brussels summit on the Franco-British plan to negotiate a peace deal with Ukraine and provide security guarantees for it, as they have held the door open to other countries’ participation such as Germany and Poland. Perhaps those talks happened on the sidelines with Macron on Thursday, but they would have happened without half of the duo in charge of the effort. At the very least, Starmer should be attending EU summits right now if he is serious about developing a sovereign European response to the collapse of American support. He has an opportunity to get it right at the Council summit in Brussels next week.

The time for timid domestic politics should be over. Starmer’s ad-hoc summits cannot be the answer here. British and EU officials need to get in a room and start quickly trying to fix the damage that was done by Brexit. There is no other alternative for a sovereign European defence that can protect us from a Russian invasion.