Europeans should be more like Americans when it comes to civics

Comparing the US Capitol visitors center to the Parlamentarium in Brussels drives home a depressing reality: Americans understand their own lawmaking process much more than Europeans do theirs.

I’ve been in Washington DC this past weekend, on my first visit back since I lived here covering the US Congress in 2005. A lot has changed since then, both for the city and for the nation as a whole. As we come toward an inflection point in US history, it was important to me while here to visit the US Capitol Building – site of the 2021 insurrection. The way things are going, this could very well be my last visit while this is still a real lawmaking institution.

The capitol visitor center under the building wasn’t open yet when I lived here, so I decided to check it out. It was an interesting time to be in the capitol, especially to see how they handled the subject of the insurrection. While it was never directly addressed, the exhibits seem to have adopted a new focus on the “disagreement and discord” in the legislature, which it stresses is part of democratic life. But in the videos featuring members of congress, there are no far-right congresspeople included. And there is no acknowledgement of what happened here three and a half years ago.

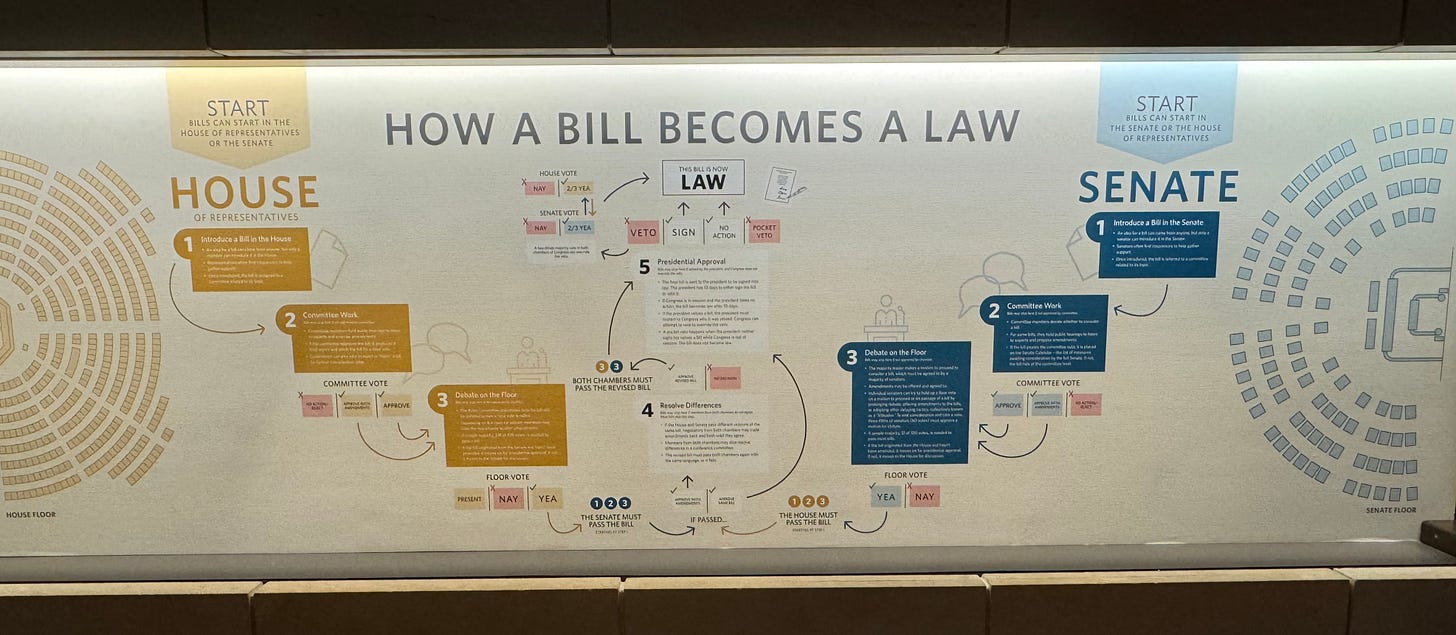

One thing that struck me was the exhibit where they explain how the legislature works – how a bill becomes a law. As I’ve written before, this is something every American is taught in civics class (what we call social studies) around the age of 14. And so most Americans know the basics: the House and the Senate each draft their own versions of a bill, those two versions are then combined in the reconciliation process, and then the president chooses to sign it into law or try to veto it. So these explanations are probably more for foreign visitors than for Americans.

As I was looking at these exhibits, I was thinking about the feedback I’ve heard from people I know who have visited the Parlamentarium at the European Parliament. It’s somethings equivalent to the Capitol visitor center, built in 2011 just a few years after the US version. It also has exhibits explaining how the legislature works, but I’ve heard time and time again from people that they left the Parlamentarium more confused about how the EU works than when they came in. The explanations are overly complicated and almost seem to deliberately obfuscate the fact that the parliament is only one part of the process of EU lawmaking. Which is not helpful on a continent where civics education is extremely limited compared to in America (because of American TV and movies, Europeans know more about how the US government works than they know about how their own federal EU level of government works - and for many Europeans, more than they even understand how their own national government works).

In the Parlamentarium, there is no simple chart like the ones in the Capitol visitor center. In fact they only talk about the parliament, which is the lower house of the EU’s legislature – leaving the Council (the upper house equivalent to the US Senate) out as if it doesn’t exist. It would be as if the US House of Representatives established a museum on its own completely ignoring the Senate. And there is nothing like the Capitol visitor center exhibit pictured below that clearly shows how competencies are split between federal and member state level.

You can explain the EU simply

While there are certainly elements of EU law-making that are unnecessarily complex or cumbersome, the basics of how EU laws are made are actually fairly easy to explain - particularly by relating it to the American and German political systems. Really, the only thing people need to know is that there are three legislative bodies and one judicial overseer. There is the executive branch - the European Commission, which one could say is equivalent to the White House (along with the giant civil service within the agencies which the White House oversees). Then there is a two-house bicameral legislature. The lower house, the directly-elected European Parliament, is less powerful than the upper house, the EU Council. And then there is the EU’s supreme court, the European Court of Justice, which makes sure the member states follow the laws passed by the EU legislature and that the EU legislature itself is acting within the law.

Like in the US Congress, the upper house (Senate) is the more powerful and the one that is meant to be more practical, where cooler heads prevail. And like in the German parliament, the lower house (Bundestag) is directly elected while the upper house (Bundesrat) is made up of representatives of each state government. Like in Germany, the political makeup of the lower house is determined by direct elections every five years, while the makeup of the upper house is determined by the elections of member states which happen at various times. This is, in fact, how the US Senate used to work before the constitution was amended 100 years ago to make senators directly elected. Until the 20th century US senators used to be chosen by the governments in the state capitals, just like they are in Germany and the EU today.

As in any other federal system like Germany’s or America’s, in the EU some areas of law are covered by the federal level and some are a competence of states. Unlike in those national federal systems however, the line between federal and member state law in the EU can be a bit blurred because of directives - a peculiarity of EU law. There are two types of EU legislation: regulations that are directly applicable on people and companies, and directives where deliverables and goals are spelled out and member states can choose how to meet them. This is why, during the Brexit referendum for instance, people were making wildly different claims about what percentage of British laws are made at federal level in Brussels - it depends how you count directives. Generally speaking, the figure we often hear is that if we count directives, about 60% of the laws that effect an EU citizen comes from the federal level - a proportion similar to the federal-state split in the US.

Beneficial confusion

All of that could be easily put on a graphic like the ones I took pictures of above in the US capitol. So why aren’t they? Why is there nothing similar in the Parlamentarium?

Obviously the European Parliament can’t compete with the US Congress in terms of the level of public interest, grandeur or consequence. But the big difference is that the visitors are coming into the Capitol visitors center with a base of knowledge of how the US lawmaking process works. Most visitors to the Parlamentarium come in with no knowledge, because their education systems (particularly in Western Europe) don’t teach them anything about how their confederal level of government works. It is in many peoples’ interest in Europe to keep the public ignorant of how EU law is made, from national politicians who like to convince citizens EU laws are being forced upon them to Brussels-based lobbyists and journalists who insist the EU is so complicated that you need to pay them big bucks to translate it for you. And part of the reason the EU Parliament virtually ignores the Council in its visitor center is because it is in a constant institutional power battle to big up its own importance. MEPs like it when the public mistakenly thinks the parliament’s version of a bill means it’s just become law.

But the reality is EU lawmaking is not much more complicated than how US governance works, with a similar split between federal, state and local law. Why then is EU lawmaking presented as something much more complicated than it actually is, even in the information center at the parliament that is supposed to explain it to visitors in a way they can understand?

Last days of Rome

Another big difference between these two legislatures’ visitor centers is the sense of permanence. The Parlamentarium presents, rightly, a European project in flux. It’s new, and it’s evolving. The Capitol visitors center, by contrast, presents the world’s oldest democracy.

Rather than presenting something that was invented just a few decades ago and is still evolving and adjusting (the EU), the Capitol presents something fixed, archaic, and unchanging. As a toga-wearing George Washington gazes down upon you from the frieze in the capitol dome, sitting on clouds surrounded by angels and virtues, it all looks so permanent - and semi-religious. How could this ancient institution ever collapse? The Parlamentarium would look absurd if it presented paintings of the EU founding fathers (some of whom are still living) sitting on clouds surrounded by angels. Indeed, the message of the museum is that this is all impermanent, vulnerable. It’s the same message that French President Emmanuel Macron had before the EU election last month: “Europe could die”. But somehow, inside the Capitol visitors enter, these grand American institutions seem somehow immortal. Which seems absurd when you’re standing in a building that was overrun by an insurrection just 41 months ago.

Washington DC is an inorganic city, purpose-built for politics on the model of a New Rome. It is the city of 20,000 neoclassical pillars, where founding fathers are dressed up as toga-wearing Roman emperors for statues. This makes these times feel all the more like the last days of Rome. Because as much as these institutions make themselves out to be immortal, they are right now very archaic and vulnerable.

It is a good thing that Americans are taught how their own government works. That is something that Europeans should emulate. That Europeans aren’t taught these basic things has been one of the most shocking things I’ve encountered living in Europe. But at the same time, Americans could learn something from Europeans about being humble and understanding governance as an impermanent project. One thing the Parlamentarium does do well is presenting EU governance as a project-in-evolution that citizens can engage with and help shape. But the way it’s presented in the Capitol visitors’ center is: this is the way it is, this is the way it’s always been, and there is no sense in even discussing whether to change it.

I’m about to board the plane back to Brussels. I came to this country ten days ago completely devoid of hope for the future for America. But the events of the past week have given me, and my family and friends who live here, a reason for hope which hasn’t been felt in a long while. There are dangerous, dark times ahead for America. But I’m leaving here more optimistic that this country can whether the storm.