Nationalism will still dent the far right's impact in the EU

Though they have a quarter of seats, far-right MEPs have split into three groups dominated by the Italians, the French and the Germans. Once again, they failed to form a 'Nationalist International'.

The new European Parliament will sit for its first plenary session of the 2024-2029 term in Strasbourg on Tuesday, and two new far right groups will take their seats. MEPs have spent the past month since the 9 June election in intense negotiations over which national parties will sit in which pan-European groups. And although before the election French far-right leader Marine Le Pen had publicly invited far-right Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni to unite their Identity & Democracy (ID) and European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) groups, the exact opposite happened. ID split into rival French-dominated and German-dominated groups, sucking MEPs away from ECR in the process.

If they had united, the far-right could have surpassed the center-right European Peoples Party (EPP) to become the largest group in the parliament. Instead, they have split into three groups that each look in danger of eventually falling below the required threshold of 25 MEPs from at least seven EU countries - which would mean they cease to exist. Once again, the egos and national interests involved meant that the biggest far-right parties couldn’t come together. Instead, we’ve ended up with Italian, French and German-dominated groups plus their small-country friends.

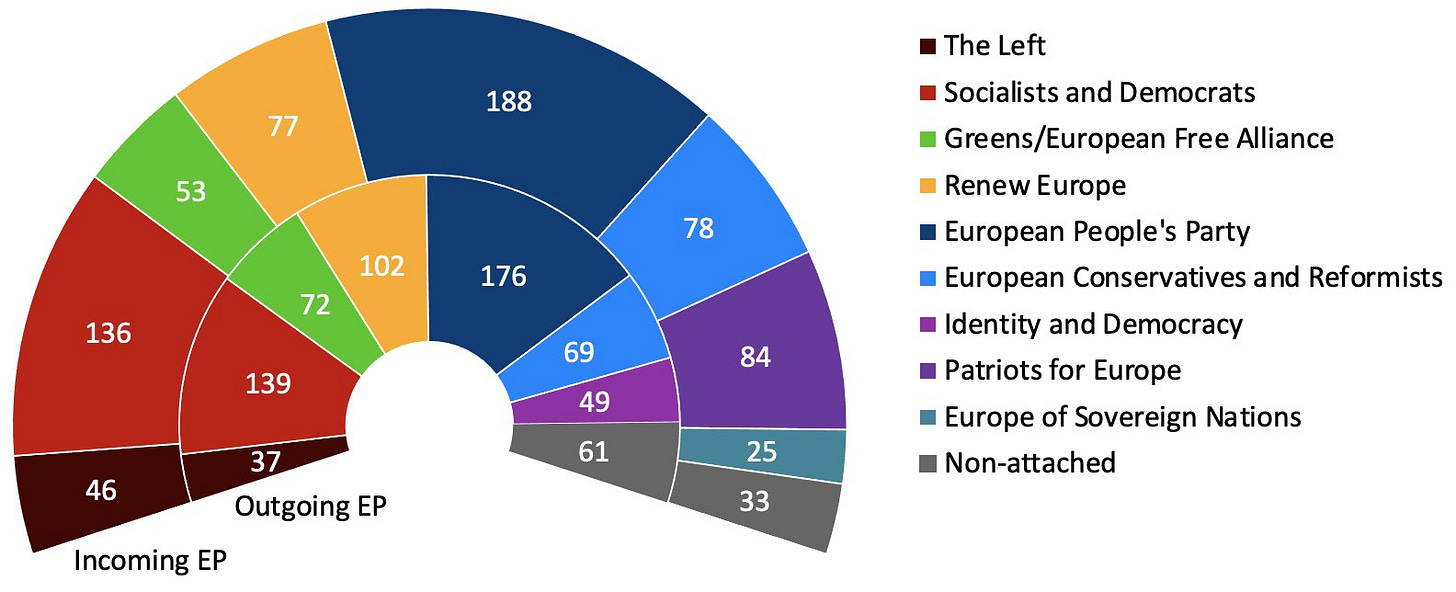

The biggest news was the creation of the Patriots for Europe (PfE) group, which is effectively a rebranded and expanded ID. They have surpassed ECR to become the third-largest group in the parliament, which surprised a lot of people including myself because it was expected that Le Pen’s national rally would be too distracted by the French legislative election to woo parties into their French-dominated ID group, leaving the ground for Meloni’s ECR to become the largest and most influential opposition group. But what ended up happening was that Viktor Orban’s Fidesz was able to do the negotiating for them, creating a rump version of PfE with non-aligned parties and then inviting the ID parties to join. But does this mean Fidesz becomes the dominant party in the new group? Numerically, it doesn’t appear so. Look at the chart below by Europolitiko.

Notice something about the black, brown and dark grey groups? They are each dominated by one big-country party. Despite the presence of limelight-seeking Orban, the French MEPs will dominate PfE just like they dominated ID (dominating without deigning to show up or take much interest in EU lawmaking). Europe of Sovereign Nations (ESN), formed at the last minute by AfD, is dominated by the Germans. In ECR’s case, Poland’s PiS (a founding ECR member, unlike Meloni’s FdI) is second to the Italians but still quite a bit smaller. Compare that to the proportions of the centrist groups. The liberal Renew Europe now has no large party at all, due to Macron’s French MEPs having a disastrous performance on 9 June. Center-right EPP is anchored by its large German, Polish and Spanish contingents. Center-left S&D is anchored by its large German, Italian and Spanish contingents. None of them are dominated by one particular country, with one bubble overwhelming all the others.

This is important for two reasons. For one, it is a continuation of a long-standing trend. Even as the far right’s size in the parliament has steadily grown over the past two decades, they have been unable to unite in a way that gives them influence in the European Parliament. As I wrote back in 2014 following that year’s election, “a Nationalist International is a tricky feat to accomplish”, certainly tricker than the Communist International was.

The other reason is that groups dominated by one country tend to be very vulnerable to collapse. ESN, hastily formed at the last minute by AfD, seems destined to fail. It is the group for far-right rejects - the parties that nobody else wanted. It has barely met the threshold, and it would only take one MEP leaving the group to cause it to collapse. Curiously, as Euronews’ Jorge Liboreiro has reported, the new Spanish far-right party The Party’s Over (SALF) was originally supposed to join the group. They were even included on an infographic distributed by ESN, but were then mysteriously gone by the time of the unveiling. The Germans may have been too toxic for them. How long can this group possibly survive?

But while there may have not been the “far-right surge” predicted by so much of the anglophone media, and while the far right may have handicapped itself by splitting into three big-country-dominated groups, as you can see from the chart below there has overall been a big shift toward the right. If you consider the Liberals to be on the left side of the spectrum, the previous parliament was roughly split 50/50 between right and left (the non-attached MEPs tend to be mostly right wing). But in the new parliament, the center right and far right together have 56% of seats. And if you consider Renew to be right of center (as many people would), then the center-left and far-left together have only a third of seats.

This means that although the center held in the election and the parliament will continue to be governed by the same centrist majority that it has been for four decades, that majority doesn’t reflect the overall movement of the parliament which has shifted to the right. The Blue-Yellow-Red coalition which will confirm President von der Leyen in Strasbourg next week (or attempt to at least, we may be in for some surprises - more on that to come) has only the thinnest of majorities.

As Euronews’ Gerardo Fortuna has noted, whatever the controlling majority is, the actual trends of the parliament are being reflected in the composition of committees - and that could have a big effect on EU legislation. For instance, the Environment Committee will now only have seven Green MEPs, compared to 11 in the previous term. By contrast, there are will now be 23 far right MEPs in this committee. While center-right EPP had to rule out allying with the far right to control the parliament (they didn’t have the numbers to do it even if they wanted to), they have left the door open to allying with the far right on a vote-by-vote basis, particularly when it comes to environment and climate legislation. With the new composition of the environment committee, they could easily shoot down future attempts for ambitious Green Deal legislation.

In short, the far right does not yet have the public support or the cohesion to make a significant difference to EU policy. For the moment, the only thing that could give them that influence is the EPP breaking the cordon sanitaire and working with them. EPP leader Manfred Weber has clearly expressed his desire to do so, but this has been met with significant opposition from others within the group.

We still have several months to go before legislative voting starts again, as the Autumn will be taken up by confirmation hearings for the new commissioners, who won’t start proposing legislation until January. But an early indication of the EPP’s intentions may come in those Autumn hearings. Will they team up with the ECR, PfE and ESN to reject commissioner nominees from Spain, France, Germany or Malta who they deem to be too left? If that happens, buckle your seatbelts. Because the only ones who could lead the far right into a united position of power right now are the center right.