The EU's next president should be a bully

In the US, much is made of the "bully pulpit" which is used by the American president to get things done in Congress. Why have all EU presidents since Delors been reluctant to use theirs?

On Monday, the eight Spitzenkandidaten (lead candidates) for the EU election on June 9th will face off at a debate in Maastricht, the city where the European Union was created in 1992. It is the continuation of debates which started when the Spitzenkandidat system was created for the 2014 election as a way to give the public a say over who becomes the EU president. But this time around, the debate is nothing short of a farce.

Out of all the candidates on that stage, only one is a real contender to become the next EU Commission President: incumbent Ursula von der Leyen. The actual spitzenkandidat system was killed in 2019 through the appointment of von der Leyen, who had not been a candidate in the election. But the European political groups have inexplicably chosen to revive the system again this year under the same name. It is entirely unclear whether these people are still being presented as presidential candidates or simply the face of the party lists for the European Parliament. The presence of President von der Leyen, who is not a candidate to be an MEP in the parliament (nor is center-left spitzenkandidat Nicolas Schmit), suggests that this is supposed to look like a presidential debate. It is, at best, confusing to voters. At worst, it is a deliberate sham meant give a democratic veneer to von der Leyen’s inevitable re-appointment. And that would more closely resemble a Russian election than a real exercise in democracy.

Von der Leyen is the only real candidate because even before the election she is already the clear choice of the 27 national leaders in the European Council, who have the power to appoint the Commission president under the EU’s treaties. The spitzenkandidat system invented in 2014 was meant to pressure the national leaders into surrendering that power and accepting the candidate from the group that won the most seats in the election. The national leaders did so in 2014 by appointing EPP candidate Jean-Claude Juncker, who had run a full campaign ahead of the election. That was despite an attempt to veto Juncker’s appointment by David Cameron, who opposed the Council relinquishing the presidential appointment power to the electorate. But for the next election in 2019, a far more powerful leader opposed the system - French President Emmanuel Macron. He refused to consider anyone who had run as a candidate in the election because it would solidify the spitzenkandidat process, and instead von der Leyen was plucked out of obscurity on his suggestion. She was appointed no in spite of not being a candidate in the election, but because of it. The Parliament, still angry at what the Council had done, only confirmed von der Leyen by nine votes (they had promised to only confirm one of the spitzenkandidats, but in the end lost their nerve). She was very nearly rejected.

Even if there were a shock election result defying all polls in June, and the center-left S&D group came first, it is inconceivable that the Council would appoint Schmit, a virtually unknown commissioner from Luxembourg. They would choose a more well-known (and more conservative) person from the center-left. Certain national politicians seem to think that the Commission presidency must always go to the center-right EPP whatever the election outcome. Even in the very unlikely event that the president in the next term is not von der Leyen, it isn’t going to be anyone else on that Maastricht stage either.

But let’s face it, barring some incredible unforeseen development, von der Leyen will still be Commission president at the end of this year. Since being appointed, she has served the Council well. She is undoubtedly the best communicator of any Commission President in history, and also has the most name recognition with the public than has ever been seen for any EU-level leader. Part of that is due to the crises which came during her first term: the Brexit cliff edge, Cthe pandemic and the war in Ukraine. She has been a steady hand throughout it all, projecting an image of calm and poise.

Who’s the boss?

Von der Leyen looks like a leader, but is she one? The hard truth is that if von der Leyen had been a real leader over the past five years, the 27 prime ministers and presidents wouldn’t be so eager to re-appoint her in two months. For them, she has the perfect mix. Unlike her predecessor, she is calm, polished and in control. She presents a dignified face for the union. But at the same time, she doesn’t challenge the member states. Her Commission has presided over the lowest (proportional) number of infringement actions against national governments for violating EU law of any term in modern history. She has never gone against Germany, her home country, or France, whose leader she owes her presidency to. Nor has she acted on parliament requests to go after Poland and Hungary, knowing that she is also dependent on them for her re-appointment. The national leaders like her because she does what they say, and she looks the part of a president while she does it.

People in the Council will tell you that this is as it should be, that the national leaders are the real executive and the Commission president is meant to do their bidding. Macron has said this is his reason for opposing the spitzenkandidat process - because the Commission president role shouldn’t be “politicized”. But the treaties (the EU’s constitution) are very unclear on this, only stipulating that the Council gives vague instructions to the Commission but the Commission is the only one who actually initiates legislation. It was this ambiguity that the notorious “Machiavelli of the Berlaymont” Martin Selmayer used in 2014 to elevate his boss, Jean-Claude Juncker, into presiding over the first “political Commission”. This is a mantra that has continued to be embraced by the von der Leyen team - on paper at least. The transition from José Manuel Barroso (perhaps the most compliant Commission president the member states ever had, hence his two terms) to Jean-Claude Juncker in 2014 marked the transition from the ‘civil service’ Commission to the ‘political Commission’.

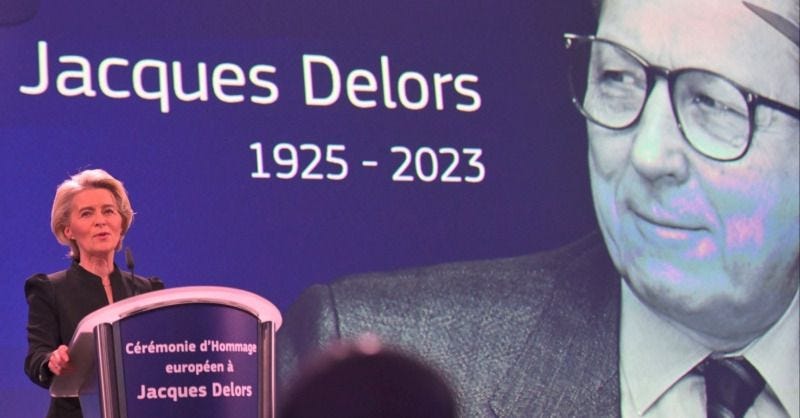

That isn’t to say the Commission didn’t have political leaders before. The institution’s most powerful president in history was Jacques Delors, who was influential in transforming the intergovernmental European Community into the confederal European Union during his leadership. He presided over the biggest transfer of powers from national capitals to EU level in history. Without him, we wouldn’t have the single market, free movement, the common currency or an enlarged union. In short, without Delors Europe would be irrelevant today. His boldness, even in the face of the usual national government intransigence, accomplished great things.

Delors passed away four months ago, and I couldn’t help but think, during all the eulogies from national leaders including Macron, that the beautiful words stank of rank hypocrisy. None of those national leaders would even consider appointing someone as strong as Delors today, because their natural instinct is to not appoint someone who would challenge them. This is the problem with the system of Council appointing the Commission President (which is the real executive presidency of the EU, not the confusingly-titled position of Council President created 15 years ago). The process means there isn’t a real separation of powers. There will always be an inherent conflict of interest for any president wishing to serve more than one term.

Pulpit unused

In the United States, the executive branch operates in many ways similarly to the EU executive. Though it is headed by a ‘political’ entity, it is in fact mostly made up of executive agencies, a vast civil service not unlike the European Commission. But there is a major difference. In a way, the EU executive is more powerful because it is the only branch of EU government which can initiate legislation. In the US, only the Congress can initiate legislation - the president can only sign it or attempt to veto it.

The US president often finds a way around this lack of power by using what has come to be called the “bully pulpit” - their ability to use their mandate from the people to pressure the Congress to do something. It is that direct (or, in the US case with the electoral college, indirect) election which is the basis of this pulpit’s legitimacy. The president is not dependent on the Congress for their position, they get their mandate from the people.

The EU president, by contrast, not only gets their mandate from the member state governments, they are also dependent on keeping the member states happy if they want to be re-appointed for a second term. The equivalent would be if the US president got their mandate from and depended on being in the good graces of the US Senate (which, until a century ago, was made up of state government representatives just like the EU Council or the Bundesrat in Germany - US Senators weren’t elected until the start of the 20th century).

Delors was the one exception to this rule, and his ability to use his bully pulpit despite his dependence on the Council (he served two terms from 1985 to 1995) is nothing short of remarkable. But they were different times - the exhilaration caused by the fall of the Berlin Wall made European national leaders more foresighted and willing to dream than they are today.

It is a shame that Macron and other leaders cannot think more of the European than the national interest in this regard. Refusing the give the Commission President a democratic mandate from the election may make sense for short-term instincts to preserve your own power. But in the long run, it sets up a situation where the president cannot use their position to pressure national leaders into doing the right thing for the European interest over narrow national interest. With the current system, you are always going to get someone like von der Leyen. Despite all of her diligence, intelligence and excellent communication skills, von der Leyen is no Delors. She is not a visionary. A visionary would be too alarming for the 27 men and women who make this choice.

The spitzenkandidat system wasn’t perfect by any means. In its first years it would have suffered from a lack of actual public knowledge about the candidates. But you have to start somewhere. Killing it off, rather than engaging with it and working to improve it, was a short-sighted and selfish act by the Council. They’ll get their von der Leyen second term. But will that get them a strong, democratically legitimate European Union taken seriously on the world stage? No. Both in the story behind her original appointment and the factors surrounding her reappointment, President von der Leyen is the living embodiment of how the Council consistently blocks EU progress.

One can imagine an EU with a bully president, someone like Thierry Breton or Frans Timmermans who has shown willingness to stand up against national governments for the benefit of EU citizens. Someone with both a mandate from the public, and the nerve to use it, would be able to use their bully pulpit to stand up against the Council when they are acting in narrow national interest rather than the European interest. In the same way that the US president can put pressure on Congress by saying '“the voters elected be to do this, you’d better get it done”, an elected EU president could say to the Council “the voters elected me to propose this, I did, don’t you dare water it down (as you always do). The citizens are watching you.”

But for the moment, imagining such a scenario is all we can do. Because as long as national leaders insist they must be the ones to select the president rather than the public, we will always end up with the lowest common denominator. The idea of Timmermans or Breton being appointed by the Council is fanciful (Breton is apparently even too intimidating to get the support of his own national president).

Who you want standing up for you against a President Trump declaring economic war on the EU, a President Putin threatening to invade, a PM Orban acting as Putin’s agent, a PM Meloni tearing babies away from their gay parents, or a President Macron seeking special treatment for France? Do you want a von der Leyen, or a Timmermans? In a world of bullies, you want a bully on your side. But von der Leyen is no bully. She’s a pushover. And you will never get someone strong enough to defend the EU from enemies within and without as long as we maintain the current appointment system for choosing the EU president.

So tune in to the Maastricht Debate if you like. But know that when it comes to the presidency, you are watching a coronation rather than an election.