The time for EU public service media is now

Trump is shutting down the pro-democracy US news outlets Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, set up during the Cold War to combat Russian disinformation. The EU should take them over and expand.

My very first job in journalism was at Radio Free Europe - an internship while I was studying abroad in Prague in 2002. I was a European history major at the time and before then had never thought about a career in journalism. But my time at RFE first planted the seeds of the idea to combine my passion for Europe with a journalistic career. I came back to the US, got a masters in journalism, and in 2006 I returned to Europe to start my career.

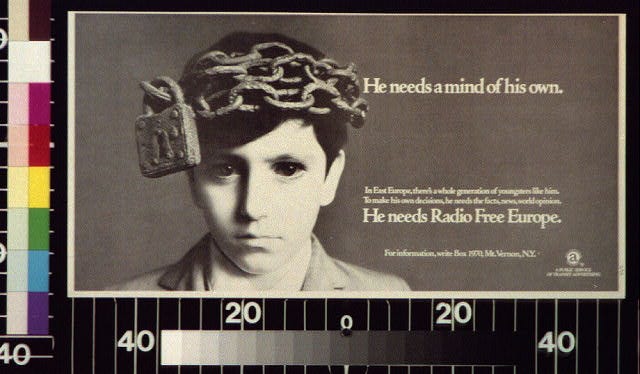

Over the weekend, the Trump regime axed Radio Free Europe along with Voice of America, ending their funding. Both were set up by the US government in the 1940s to combat Russian propaganda during the Cold War. Radio Free Europe was based in Munich and sent radio signals across the iron curtain to Eastern Bloc listeners, giving them an alternative to the Communist state-controlled media. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, RFE faced the same question as NATO - now what? The US government decided to continue its operation, moving it to Prague in 1995 and continuing broadcasts into the former Communist countries. It was still unclear whether media freedom in all these countries would last (spoiler alert: it didn’t). RFE’s remit then expanded to the Middle East, broadcasting in Arabic and in Persian into Iran. They have continued to be vital for getting free information into Belarus and Russia, where the activity of journalists is restricted. RFE broadcasts in 27 languages to 23 countries.

Announcing the cuts, de-facto American Chancellor Elon Musk called RFE "radical left crazy people talking to themselves while torching $1 billion a year of US taxpayer money". The news has prompted a furious reaction from journalists and European politicians. RFE’s president Stephen Capus called it “a massive gift to America's enemies". "The Iranian Ayatollahs, Chinese communist leaders, and autocrats in Moscow and Minsk would celebrate,” he said. The Committee to Protect Journalists issued a statement warning that thousands of journalists will be out of work as a result of the cuts, and those working in countries with censorship will be put "in grave danger". The Brussels-based journalists union API (of which I am a member) called it “a serious setback for independent journalism and the principles of press freedom.”

As journalists, we might have a knee-jerk reaction to preserving any media funding even if it doesn’t make sense. At first glance, an American taxpayer might ask four valid questions about why the US should continue to fund these outlets:

If they were set up to fight Communism, why did they continue operations after 1992?

In the digital age when citizens of authoritarian regimes can get around censorship using VPNs, what is the point of sending radio signals across borders?

Why is the US sending propaganda to other countries?

Why should America be responsible for free European media rather than Europeans?

I have good answers to all of these except the last one. For question one, while I think it would have been a good idea to rename and rebrand RFE in 1995 to lose the impression it was an anti-Russian vehicle (you could make the same argument for NATO), with hindsight we can see that free media targeting people in authoritarian regimes remained very necessary even with the collapse of Communism.

For question two, the radio broadcasts into authoritarian regimes are still very useful for poor and elderly people who don’t have access to the internet. And RFE’s work is now largely online in web articles, providing invaluable sources of real information in contrast to regime media. Yes a savvy young person in Kazakhstan can access CNN.com, but when is CNN ever going to cover Kazakhstan? RFE provides for a dedicated Kazakh service employing Kazakh journalists doing broadcasts and writing articles. Without this service, the only alternative people in countries like that will have is their regime media. There simply isn’t commercial viability for something in the private market to take on lavishly funded state media in these places. Yes the internet means that some part of the population has access to free media, but if that media isn’t covering their country, that isn’t helping them is it?

For question three, Americans may not be aware that most other wealthy countries already have this type of government-funded public service media intended for other countries. The UK has the BBC World Service, which broadcasts in 40 languages around the world and operates very much like RFE, financed by the Foreign Office budget rather than by the BBC’s TV license. Germany has Deutsche Welle, who I used to work for, and France has France 24, who I work for now. More importantly, authoritarian regimes have also established their own international broadcasters, most notably Russia Today (RT) which broadcasts in eight languages including English, Spanish, French, Arabic and Serbian. China has CGTN broadcasting in various languages around the world, and Iran has PressTV. Turkey has TRT World, and Israel has i24News. All of these broadcast in English. Some, like RT and CGTN, are tightly state-controlled propaganda. Some, like TRT World, RFE and i24News, exist in a grey area where the state control isn’t explicit but government influence is detectable. Others, like BBC World Service, France 24 and DW, are shielded from state control. The idea is that international public service broadcasters like the latter three actually end up being more free from bias because their public funding means they aren’t subject to commercial pressures. So it isn’t unusual that the US has such a media service, most wealthy countries do.

That brings us to question four, for which I do not have a good answer. The key difference here is that while all those other public service international broadcasters are global, RFE is targeted at a specific geographic area which the paying country is not part of. One could make the argument that Russia Today English was specifically set up to target Americans and destabilise the country in an act of revenge for what Radio Free Europe did to the Soviet Union and its satellites. But they are also broadcasting to other parts of the world that are not America. RFE and VOA can therefor feel like relics from the Cold War. So it leads to the question, why should providing free European media be the responsibility of Americans rather than Europeans?

Time for European media sovereignty

At yesterday’s meeting of EU foreign affairs ministers here in Brussels, Czech foreign minister Jan Lipavsky raised the issue, saying RFE "is one of the few credible sources in dictatorships like Iran, Belarus, and Afghanistan". He proposed that the EU take over the broadcaster to save it from closure, and according to Council sources six other foreign ministers backed the idea. The supportive countries include Germany, the Nordics and the Baltics. Following the meeting, EU foreign affairs chief Kaja Kallas said it might be possible, but it would be complicated.

"Can we come in with our funding to...fill the void that U.S. is leaving? The answer to that question is...not automatically, because we have a lot of organisations who are coming with the same request to us," she told reporters. "But there was really a push from the foreign ministers to discuss this and find the way, so this is the tasking to our side, to see what can we do."

In my opinion, the European Union should already have been thinking about taking charge of its own media sovereignty years ago, just like it should have been thinking about taking charge of its own military, economic and cultural sovereignty. I and others have long been calling for EU public service media not just to combat Russian disinformation, but also to combat the Anglo-Saxon dominance of the international news media. This was actually the subject of my very first post on Substack, in which I argued that the EU is letting the British and Americans tell their story, and that story is being told in a distorted and biased way.

Wolfgang Blau, the former Chief Operating Officer of Conde Nast, was one of the first people to start putting this idea into the European consciousness with a Medium post in 2020. “Currently, the ‘stories’ of the EU — the European Union’s history, its raison d’etre, its current challenges and future options — are told to the world primarily by UK media organisations whose global audiences and social media accounts — as crucial vehicles for content distribution — dwarf most continental European news organisations,” he wrote. The US media takes their cues for coverage of Europe from the British media (because only three major US media outlets have correspondents in Brussels), and the world receives its news about the EU through an Anglo-Saxon lens which has often been hostile or biased. It says a lot that it took an American company (Politico) to finally make a big investment in Brussels journalism in 2015. No Europeans media company has been willing to do so.

Debunking the myth of UK and US media's 'neutral gaze'

In feminist theory, the concept of the “male gaze” has been coined to describe how media and literature portray life through the eyes of men as the neutral point of view, while the perspective of women is othered. For years women have consumed media that always puts the male perspective first, for instance by sexualizing women but not men. In that way t…

Trump’s closure of Radio Free Europe therefor offers a very interesting opportunity to finally make a major EU investment in journalism by Europeans covering the European Union in English, the world’s langua franca. It comes at a time when the European Commission has been ending its (already paltry) funding for Brussels-based news media over the past years, which has recently resulted in a rightward drift as Brussels media had to go looking for funding elsewhere including from sources linked to Viktor Orban. Employees of these Brussels media institutions which have recently had dramatic changes in management have let their feelings be known, but it has made little difference in a world where these outlets are subject to commercial whims and market pressures which tell them the best course of action is to ride the wave of right-wing populism.

Could Radio Free Europe provide the skeleton on which to put some real meat on the bones for an EU-funded public service media that is shielded from the commercial considerations which seem to be already driving so much of the English-language media into compliance or obedience? Kallas is right that it wouldn’t be easy. RFE was already operating on a shoestring budget and their presence in Brussels has been minimal. But if all of these national governments (including EU members as well as EU adversaries) have public service media that seek to provide a certain point of view, why shouldn’t the EU? Indeed, when Russia and China are pumping disinformation into the EU with their international broadcasters, it seems like a dereliction of duty for the union not to have any response.

I hope that Kallas was serious when she said that the European External Action Service is going to take a look at whether this can be done. I worry that with everything else going on this is not going to be a top priority. But if the EU is about to make a major investment in its sovereign military security (as will be discussed at the European Council summit on Thursday), some of that money should also be going toward sovereign information security as well. Achieving European independence isn’t going to be possible with just tanks alone.