What the hell just happened at Eurovision...again?

The song contest's new lax rules for public voting seems to have resulted again in votes being cast by people who haven't watched the show but want to make a political point. Eurovision is in trouble.

This was a busy weekend of voting, and oddly enough the biggest scandal didn’t come from the closely watched elections involving the far right in Romania, Poland and Portugal on Sunday but rather the Eurovision Song Contest televote on Saturday night. While the scandal wasn’t as big as last year’s disaster, the unavoidable truth that the televote has become a tool to make political points rather than an assessment of the public’s favourite songs became glaringly obvious at the end with the most uncomfortable final two face-off in Eurovision history. Several broadcasters including Spain’s RTVE are requesting an audit to determine what happened in the televote and they are asking for changes in how it’s conducted. Belgium’s broadcaster announced today they will pull out of the contest unless changes are made to the televote rules.

[Update: by 22 May, 9 other broadcasters had followed suit]

I’ve wanted to stay away from this topic this year because, initially, it seemed like the controversy had died down a bit compared to last year. There seemed to be a consensus from the fans to try to grin and bear it. But there was no ignoring what happened Saturday night, when yet again Israel’s worldwide get-out-the-vote campaign succeeded in overwhelming the public televote, in which the country came first. That then resulted in the hugely damaging spectacle of a split-screen between Israel and Austria at the end to find out who between the two of them would win, as fans sat with their hearts in their throats knowing that if Israel won, that would likely be the end of the contest (more on that below explaining why). Israel’s song was fine, and in a normal year it would have likely come somewhere in the middle of the contest.

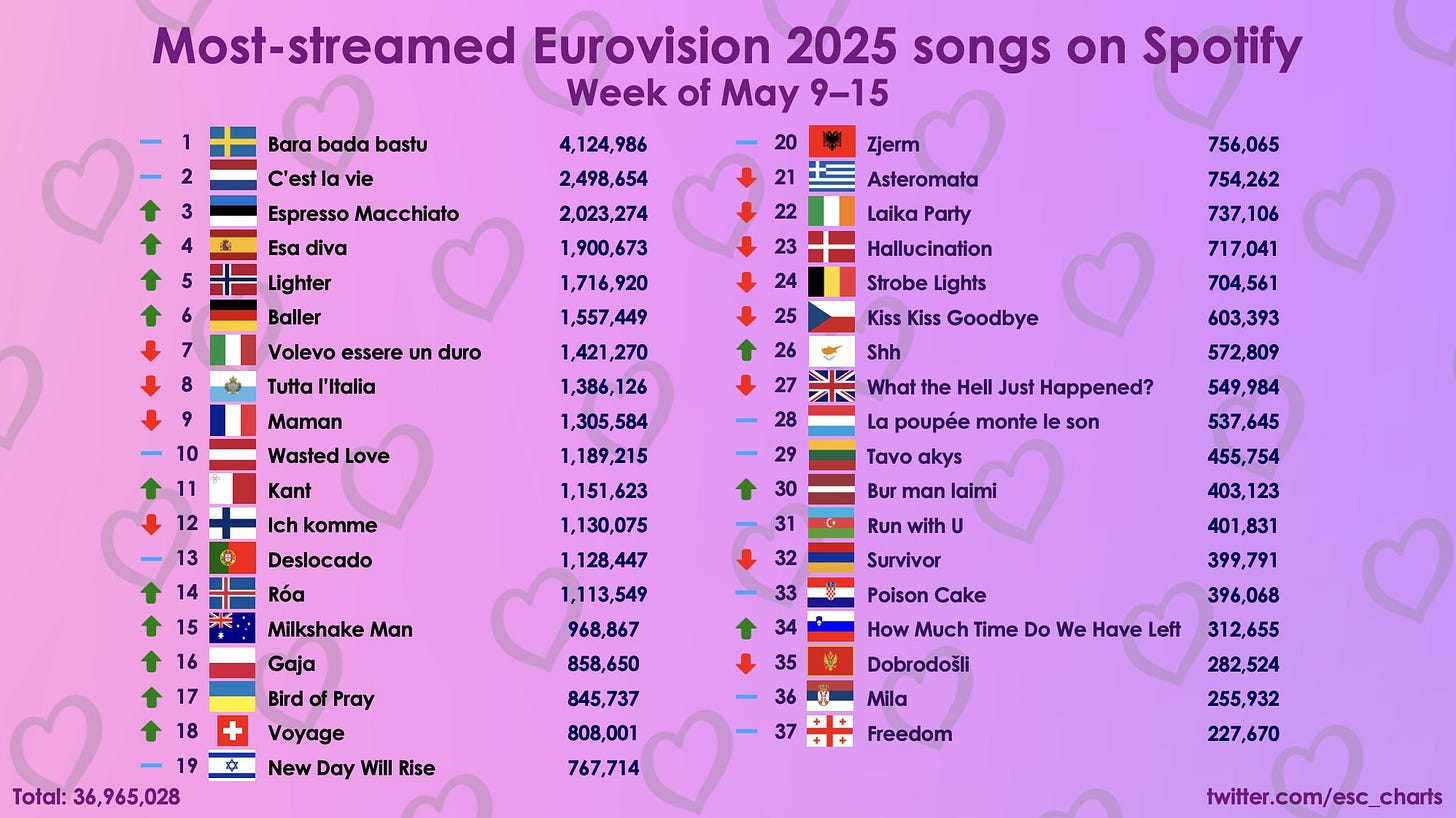

It stretches credulity to say the song would have scored where it did if it was from any other country. The juries of music experts (which account for 50% of each country’s vote) put it 15th, and the song was nowhere near the top of the Spotify stream ranking ahead of the contest. An initial investigation by VRT found that though viewership of the final in Belgium was one-third lower than viewership of semi-final one (in which Belgium performed but not Israel), the televote was six times higher in the final where people could vote for Israel. In short, the televote result does not seem to have had a correlation with the number of viewers or the actual interest in the songs. Just like with Ukraine in 2022 (another mid-level song that had no business scoring so high), we see that politics is now driving the public vote in a way never seen before in Eurovision’s history. It is becoming a major problem that would lead to the contest unravelling if countries start pulling out. And, as outlined below, it’s the same pattern we saw last year following the voting changes that were made several years ago that allow people to vote up to 20 times and make it easier for people not watching the show to vote.