Can Europe ever shed its cultural dependence on America?

Trump has threatened to impose a 100% tariff on imported movies. Given that two-thirds of the movies, TV and music consumed in Europe come from the US, what would happen if the EU retaliated in kind?

Today the 78th Cannes Film Festival begins in France, and as usual it is highlighting many small European films that wouldn’t ordinarily get much attention in American theatres. For seven decades the festival has stood as an alternative to big-budget Hollywood movies, showcasing among its offerings European films that are normally seen in America by a small number of people at arthouse cinemas. It is an international festival, but given its location it heavily features European content.

Looming over Cannes will be the bombshell announcement dropped by President Trump earlier this month that he wants to slap 100% tariffs on films produced outside the United States. While there is serious doubt about whether he has the ability to put tariffs on these types of services, particularly by citing foreign films as “propaganda” representing a national security threat, the threat has prompted a wider discussion over a dependence Europe has that not many people talk about. Much has been said about Europe’s military and economic dependence on the United States, but Europe also has a cultural dependence. Hollywood has been the chief instrument projecting American soft power throughout the world, and it is the main reason that English has become the lingua franca of Europe today. The threat to hobble this powerful tool for spreading American power thus seems particularly perverse by the US president. It is Europe that has a trade deficit with the US in this area, not the other way around as Trump seems to be bizarrely suggesting.

But as Europe discusses retaliation for Trump’s various other attacks, responding to this one would be quite tricky because it is perhaps the greatest dependence of them all. What would happen if Europe responded in kind, slapping a 100% tariff on American movies? Would Europeans be willing to pay twice as much to see an American film?

Two-thirds of the film, television and music Europeans consume come from the United States. The proportion varies from country to country depending on the size and cultural influence of their languages. For instance, the proportion is lower in France and Spain than it is in the Netherlands or Poland. Nevertheless, it is high everywhere - particularly for movies. 70.1% of cinema tickets sold across Europe in 2023 were for US films, according to the European Audiovisual Observatory. According to cinema statistics from the European Commission, that average of 70% is the level for German and Italian cinemas, while in France the proportion is 50% - largely as a result of the Toubon Law setting a quota for French-language content. In the Netherlands, the proportion is 90%.

It isn’t just movies. More than half of the television shown on European screens comes from the US, according to the Observatory, usually American scripted dramas and comedies while the current affairs, game shows and reality TV is domestic. In 2023, 60% of chart music in Europe was produced in the US. The proportion is highest in countries like the Netherlands, Denmark, Ireland and Czechia while it is the lowest in France, Spain and Italy.

Europe’s common culture is American

The culture that binds Europeans together is American. With a few notable exceptions like the cultural exchange between Spain and Italy, Germany and Austria and Ireland and Britain, each European country consumes two types of media content: their own and America’s. The culture Europeans share with Europeans from other EU countries is therefor American, and this is largely what has made English the common tongue for communication between them.

As I’ve written before, this continent is so thoroughly culturally owned by the United States that Europeans almost feel like they are part of America (and this is a phenomenon that becomes more true the younger a person is). If they turn on the TV, there’s American content. The radio? American songs. Go to a movie theatre? There’s Hollywood. Open a European newspaper and it’s dominated by coverage of American news. Europeans nations have grown further and further apart from one another as they became more and more culturally dominated by the United States. They are inundated with news from America but get no news about the countries next door to them. This is why Europeans tell me that when they visited New York for the first time they felt like they had already been there, because they have been bombarded with depictions of it from the moment they were born.

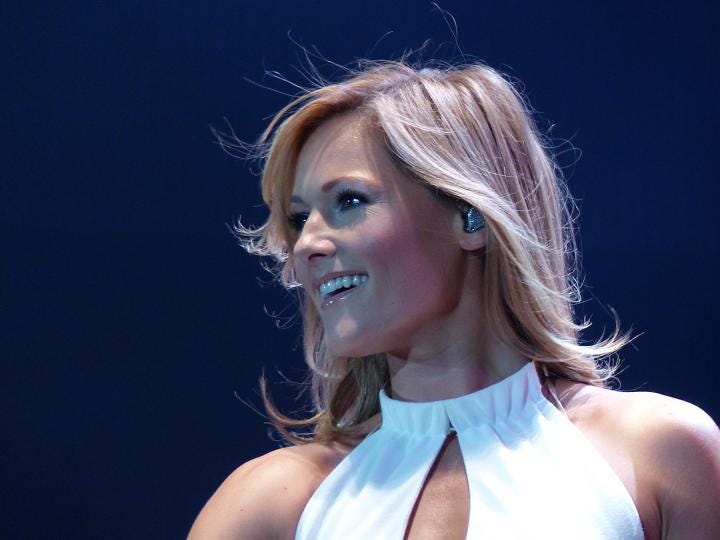

If a European musician wants to become famous throughout Europe they need to go to America first if they have any hope of then beaming back to other countries on their home continent. There is little cross-cultural exchange. What usually bonds young Europeans is that America gives them a shared sense of belonging to a common culture. Europeans bond over Friends and Beyonce, not Dix Pour Cent and Helene Fischer (the richest pop star in Europe no one outside the Germanic world has heard of). Nevermind the American military protectorate over Europe. It is not just European soil that is occupied by the Americans, it is also European minds. America’s cultural domination has made it inconceivable to Europeans that Americans might not be their friends, might be vulnerable to democratic collapse or civil war, or might even become an enemy of Europe. And this is a big part of why so many Europeans have been unable to accept what their own eyes and ears have told them over the past months: that America is no longer their ally. American cultural dominance is not harmless. It’s not a sideshow. It actively weakens Europe.

Needless to say, this is not a bilateral cultural flow. Most Americans will have never seen a European film or TV show in their lives. If they have, it is almost certainly British. According to the observatory, there were only 4.8 million tickets sold in America for European movies in 2023, 0.5% of the overall 819.3 million tickets sold. This is what makes Trump’s rant about movies all the more bizarre. “The Movie Industry in America is DYING a very fast death," he wrote on his Truth Social platform, complaining that other countries “are offering all sorts of incentives to draw" filmmakers and studios away from the US. "This is a concerted effort by other Nations and, therefore, a National Security threat. It is, in addition to everything else, messaging and propaganda!”

Foreign shooting

Last month I visited one of the foreign film lots Trump is accusing of luring American production out of the country - Atlas Studios at Ouarzazate in Morocco (pictured above and below). Many big-budget American films have been shot there over the past decades including Lawrence of Arabia, The Mummy, Aladdin, Game of Thrones, Kundun, The Hills Have Eyes and Gladiator. It makes an ideal filming location because of the blue sky, the desert backdrop, and the locals who can play extras for films set anywhere in the Mediterranean, Middle East or Latin America. Such films would be much more expensive, and much more difficult, to shoot in the United States.

European film producers told Variety last week that they don’t think such tariffs are enforceable because these are services rather than goods, whether they are European films trying to export to the US or American films shooting in Europe. “Technically, films are services on which you can’t impose tariffs - it could end up in court and take months,” an “important figure in France who runs a top festival” (probably Cannes) told the magazine. “We don’t sell goods, we sell a service, so I don’t see how it could be taxable,” said a French movie producer. But here’s the problem that the movie producers don’t seem to be aware of: services are exactly what the EU is considering imposing retaliatory tariffs on as a nuclear option in the event of a full-blown trade war. And the Commission has been arguing that it is indeed legally possible to tariff American services imports (which the EU has a major trade deficit with the US on) like banking, entertainment and and social media.

It is American companies that stand to lose the most if the trade war spreads to the area of services. A prominent Madrid-based movie sales agent told Variety, “American companies could be the biggest losers in this trade war, since sales of American films in Europe do represent a large percentage” of their profits. He said if countries respond by imposing a 100% reciprocal tariff on productions that shoot in the US, the end result could mean that they turn away from Hollywood films. “European distributors may increase their share of European films and the production and exploitation of local content.”

Even if Trump isn’t legally able to impose his movie tariff, we’ve seen so far that even the threat to do things that he can’t actually do often results in premature concessions. Already Europe’s film industry is worried that the EU and national governments might offer to scrap hard-won legislation mandating European content quotas as an offering to convince Trump to back off the movie tariffs. “We don’t want to be part of the overall negotiation on tariffs between Europeans and Americans,” Juliette Prissard, General Delegate of Eurocinema which represents European film producers, told Euronews last week. “If Europeans can no longer make films outside the US, it becomes absurd,” André Buytaers, president of the Belgian federation of audiovisual and film creators and performers, told Euronews. He added that, “in any case, there are very few European films in circulation in the US, so the impact on Europeans will not be huge.”

But this isn’t just about the small number of European movies that are viewed by Americans (particularly since the Americans that watch them tend to be wealthier and would be more willing to pay a tariff premium). The loss of the quotas would remove the incentives that have recently been put in place for streaming companies like Netflix that have resulted in a dramatic increase of European TV for European consumption recently. Shows like Casa del Papel produced in Spain for Netflix or Borgen from Denmark, also on Netflix, have for the first time started to give TV shows produced in Europe a significant reach across Europe and even in America - thanks to Netflix’s significant investment in dubbing into English, something never done before on a major scale. If the EU or national governments were to surrender the quotas as a way to make Trump back off his movie tariffs, it would mean these European productions would likely no longer be made. That doesn’t just impact the small offering of European cultural exports to the US, it also impacts the amount of European productions that have the scale and investment to reach other countries in Europe.

The European producers have reason to be worried because we know that the end of these quotas is in the American crosshairs. The Motion Picture Association of America, which represents the US film, television, and streaming sectors, wrote to the Trump administration on 11 March complaining about EU legislation imposing quotas requiring 30% of the video on demand services operating in the EU to be Europeans works. They also complained about similar national requirements. The EU’s audiovisual legislation was also highlighted as a barrier to trade by a US trade representative’s report published on 2 April.

Can Europe be culturally sovereign?

It is hard to imagine any European politician having the nerve to enact a retaliation policy that would result in a doubling of the price for 70% of the movies Europeans see. If Europe suddenly couldn’t import American film, television and music the TV screens would go blank and the radio would be silent. But after that initial shock, Europeans would need to start producing their own content to make up the void - and they could produce content intended for the EU as a whole.

The reason why America established itself as an entertainment juggernaut which then spread its cultural imperialism throughout the world is not (just) because Americans are more creative and entrepreneurial than Europeans. It is also because they benefitted from a large common market which gave the financial inventive to invest in major productions. In 1950s Hollywood, a film producer knew that a blockbuster movie he produced had a potential domestic reach of 166 million people. A French film producer at that time knew that his movie could only reach a domestic audience of 43 million people. The initial big boom of investment in Hollywood eventually led to a rapidly developing export market to countries around the world who could not afford to make such expensive movies themselves. Over time, this resulted in a situation in Europe where countries stuck with either artistic films or very low budget and low-intellect movies for the fare they produced themselves, and left it to the Americans to produce the big-budget movies shown in their theatres. The low-budget ones never left the country, and the artsy ones went to Cannes and little arthouse cinemas in the US, watched by the handful of Americans willing to read subtitles.

But it didn’t have to be that way. The genesis of this situation simply came because of the unilingual common market that the US had and Europe didn’t. As the EU seeks to integrate its common market economically, serious thought should be given to how the union can be better integrated culturally - without the help of imported American culture. The liberal free marketeers won’t like it, but experience shows that quotas do work in this regard. Just contrast Germany (which produces very little in the way of its own culture) and France (which is a cultural juggernaut by European standards). Just look at how the hard-won quotas for streaming services has resulted in unprecedented viewership of European content by people in other European countries. But the effort has to be about more than just quotas. It has to be about greater cultural exchange and setting up more pan-European cultural platforms. And yes, this has to be done in Europe’s lingua franca - English. That is unavoidable, not necessarily for the content, but for the platforms and the exchange.

This is Eurovision week, with the first semi-final airing tonight at 9pm CET. And so it’s as good a time as any to point out that Eurovision is the only successful multinational popular culture output that Europe produces without any involvement of America. Europe’s wildly under-appreciated annual song contest (most Europeans are shocked when I tell them it has more viewers than the Superbowl, Oscars and Grammys combined) should serve as a model for how Europe can bypass their American cultural overlords. It is a platform in English (the language always spoken by the hosts now), but the songs are increasingly not in English (as I wrote last month, this year has the highest number of voluntarily-chosen non-English songs in the contest’s history). Unfortunately, the instinctual European reaction to Eurovision is cultural cringe. Surely all the songs must be terrible because they’re European, they assume. Take any of the best songs from each year, put them in the mouth of Miley Cyrus or Taylor Swift, and Europeans would be calling them masterpieces.

Europeans first need to learn to take pride in their own pop culture output, and they need to ween themselves off of the addictive American entertainment drug. We need less Beyonce on this continent and more Eleni Foureira. I for one am all for paying twice as much for American content - it simply means I would stop watching and listening to it. There should be a feeling of European patriotism in rejecting American cultural imperialism. I know most Europeans aren’t with me on this yet, and that’s why we need to start having an open conversation about this. It starts with acknowledging some uncomfortable truths about how much this continent is culturally dominated.

Eurovision turns its back on English

As much as the European Broadcasting Union claims that it isn’t, we all know that the Eurovision Song Contest held each year since 1956 is very political - and no year was that more evident than in 2024. The EBU’s ban on Russia’s participation after its invasion of Ukraine in 2022 crossed a Rubicon of mainstreaming politics in the contest. It later expo…