Belgium finally has a government - and the new prime minister doesn't think Belgium should exist

After eight months of torturous negotiations, a right-wing government has been formed with the Flemish separatist party N-VA, a member of Giorgia Meloni's European alliance, at the helm.

Belgium will finally see an end to another of its notorious spells without a government next week, as five parties agreed a deal last night to form a right-wing government following June’s inconclusive election. By Belgian standards, eight months is actually not that long - the famously ungovernable county holds the record for the longest period without a government at two years (2010-2012 and 2018-2020). But the biggest complication of this election was the unexpected collapse of the Socialists, who had enjoyed unchallenged dominant rule in Wallonia for decades. MR, the nominally liberal Francophone party which has become increasingly right-wing and anti-immigrant under its new leadership, replaced them and has joined this right-wing government. But this coalition will make for strange bedfellows. The new prime minister, Flemish separatist Bart de Wever, has derided Francophones and famously said “Belgium has no future”.

A refresher: Belgium has two different language communities with roughly half of the population each, the French-speakers in the South and the Dutch-speakers in the North (plus two villages of German speakers next to the Eastern border). A century ago, the Dutch-speaking region of Flanders was the poor one, and the French-speaking region of Wallonia was the rich one. But that all flipped mid-century, when the mines in the south were mined out and Wallonia was left with massive unemployment, while Flanders built a successful services and maritime shipping economy. Starting in the 1960s the formerly unitary country was progressively federalised, to such a dramatic extent that today it feels like a country in name only since the three regions (Wallonia, Flanders plus multilingual Brussels) are almost entirely self-governing.

The two things that have remained national are foreign policy and taxation, and that last one is what the Flemish are mad about. Wallonia, with unemployment levels approaching Spain’s at around 9%, is massively subsidized by taxpayers in Flanders, which has an unemployment rate hovering around 3%. Because of Belgium’s massively generous social welfare system, many unemployed in Wallonia prefer to live off their unemployment checks than to learn Dutch and commute or move to Flanders. Walloons generally do not speak Dutch, as they prefer to learn English if they choose to learn a second language. And Flemish people resent that intensely. The result has been that Flanders has been dominated by the right (first the center-right, now replaced by the hard and far right) and Wallonia has been dominated by the left (the Socialist Party remains nominally part of the center-left PES at European level but in reality they are so far left as to be practically Communist by Flemish standards).

And that brings us to last night’s deal. The leading party in the government will be the hard-right Flemish separatist New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), and its leader Bart de Wever will become Belgian prime minister. The Francophone center-right Reformist Movement (MR), Francophone centrist Les Engagés, Flemish center-right Christian Democrat and Flemish (CD&V) party and the center-left Flemish Vooruit party will form the rest of the five-member governing coalition. In Belgian tradition, which names coalitions after random flags from around the world, they have dubbed this the “Arizona coalition” after the US state’s flag. This agreement did not come from a sudden burst of goodwill, it came because they had run out of time. Belgian King Philippe had set a deadline of yesterday to form an agreement or he would call a new election.

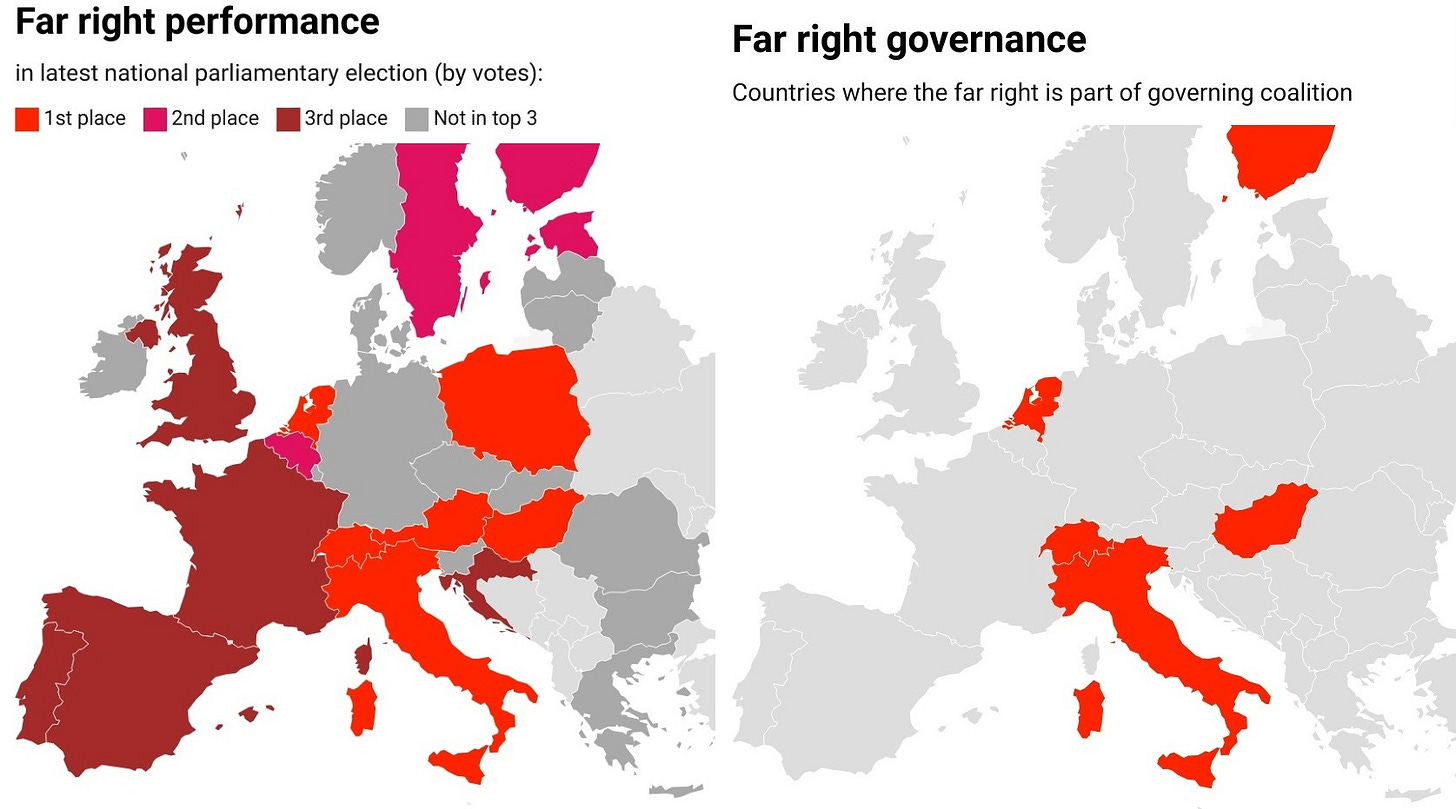

How to classify this new government is going to be tricky. N-VA sits in Giorgia Meloni’s far right (sometimes called “hard right”) European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group in the European Parliament. But N-VA can’t be said to be as far-right as its current and former ECR partners Brothers of Italy, Vox, AfD, True Finns, Greek Solution or Sweden Democrats. Nevertheless, De Wever’s premiership will on paper give the far right it’s fourth seat in the Council along with Italy, Hungary and the Netherlands, most likely soon to be joined by a fifth (Austria). However domestically in Belgium, the N-VA these days is considered to be center-right (although that’s a new development, see more on that below). Meanwhile the European affiliation of the second-biggest party in the government, MR, has the opposite issue. Its European affiliation with the Liberals (Macron’s Renew Europe) makes it seem more centrist than it actually is these days, as anti-migration firebrand Georges-Louis Bouchez has dragged it to the right over the past five years.

Further complicating matters is the fact that while N-VA sits in the EU Parliament with the far right, at pan-European level it is a member of the European Free Alliance (EFA) along with the Catalan and Scottish separatists, both of which are hard left. This will be the first time in history that a separatist EFA member sits in the European Council. And that, really, is the most incredible thing about yesterday’s news. On paper, Belgium will now have a prime minister who thinks Belgium should not exist. When I first moved to Belgium in 2010, Bart De Wever and the N-VA were still considered extreme, and the prospect of him ever becoming prime minister ruling over a county 50% composed of the francophones he vilifies would have seemed ludicrous.

N-VA emerged in 2001 from the right-wing faction within the Volksunie party which had existed since 1954 as a catch-all Flemish nationalist movement encompassing various parts of the political spectrum. N-VA states a maximalist position of Flemish separation from Belgium but its policy goals have always been actually focused on confederalism, most importantly making taxation regional rather than federal. Its original motto “evolution, not revolution” sums this up. Nevertheless, the rhetoric party leaders and in particular De Wever has used against Francophones has often sounded more like far-right nationalists, something that appeals to a lot of Flemish people and which propelled De Wever to become the mayor of Flanders’ most separatist town, Antwerp, from 2012. De Wever grew up in a Flemish nationalist household, and his grandfather was the secretary of the Flemish National Union, a collaborationist Flemish far-right party during the interwar period that was recognised by the Nazis as the ruling party of Flanders during the WWII German occupation. De Wever famously said “Belgium has no future” in a 2010 interview. But he also said, "I'm not a revolutionary, and I'm not working toward the immediate end of Belgium" but rather he believes the Belgian state is in a process of coming to an end. De Wever has also spoken in favour in the past of the Greater Netherlands concept in which Flanders and the Netherlands could potentially be united into the same country or under a federal agreement, arguing that Dutch and Flemings are "the same people separated by the same language.” However this idea is unpopular in Flanders (while Dutch people seem to be rather indifferent to it).

To an outsider, it might seem hard to believe that a man who has openly said he wants to end Belgium could be considered a centrist in this country. But N-VA has come to look more and more centrist not because they have changed their positions, but because of the rise of the extremist far right Flemish separatist Vlaams Belang party, which came second nationally in June’s election. It is the successor to Vlaams Blok, which was banned in 2004 for espousing racism. It wants immediate Flemish secession from Belgium and the expulsion of Muslims from the new nationalist state. But like most of Europe’s far right parties these days, it has recently toned down its rhetoric and bristles at the label of “far right”. 14% of Belgians voted for them in June. But there is still a cordon sanitaire against them at federal level, including from N-VA.

The deal reached last night must still be confirmed by a vote of the five parties’ membership next week. If that goes through, we can expect a highly moderated Prime Minister De Wever to present himself as a leader for all Belgians. He is part of Meloni’s group after all. But even if N-VA governs in the same moderated way in which they are presenting themselves, what will it mean for the psychology of this country to be led for the first time by a man who thinks Belgium should not exist? For a place which already feels like a country in name only, where Flanders and Wallonia have drifted further and further apart to the extent that their citizens seem to have nothing to do with each other these days, how does this impact that psychology? And how long will the francophone parties be content to serve under a man who has said very negative things about francophones in the past? This new Belgian government may only be living on borrowed time. But everyone from the king on down knows the alternative. If new elections are called, Belgian voters will move even more toward the extremes.